The Republic of the Gaze

- Oct 21, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Nov 30, 2025

There are regimes of the gaze just as there are political regimes. Some command the light, others nurture the darkness. Within the cities of images, each person holds a place: the viewer and the actor, the master and the model, the body and its reflection. It is the framework of this latent order that La dictature du modèle (The Dictatorship of the Model), an exhibition on view at Galerie Flux until November 1, 2025, brings to light. It brings together the works of three photographers (Michel Hanique, Jean-Marie Boland et Didier Gillis) around a shared motif: the female nude.

Since the dawn of Western art history, the female nude has held the privileged position of a mirror through which society projects its relation to the body, to desire, and to beauty. As a symbol of origin and harmony, it has also been the scene of imbalance: the locus of a masculine gaze that shapes form, situating woman within the image rather than within being. In this regard, the nude has never been neutral. It is a field where the tension between representation and power, between the act of seeing and the will to possess, endlessly plays itself out.

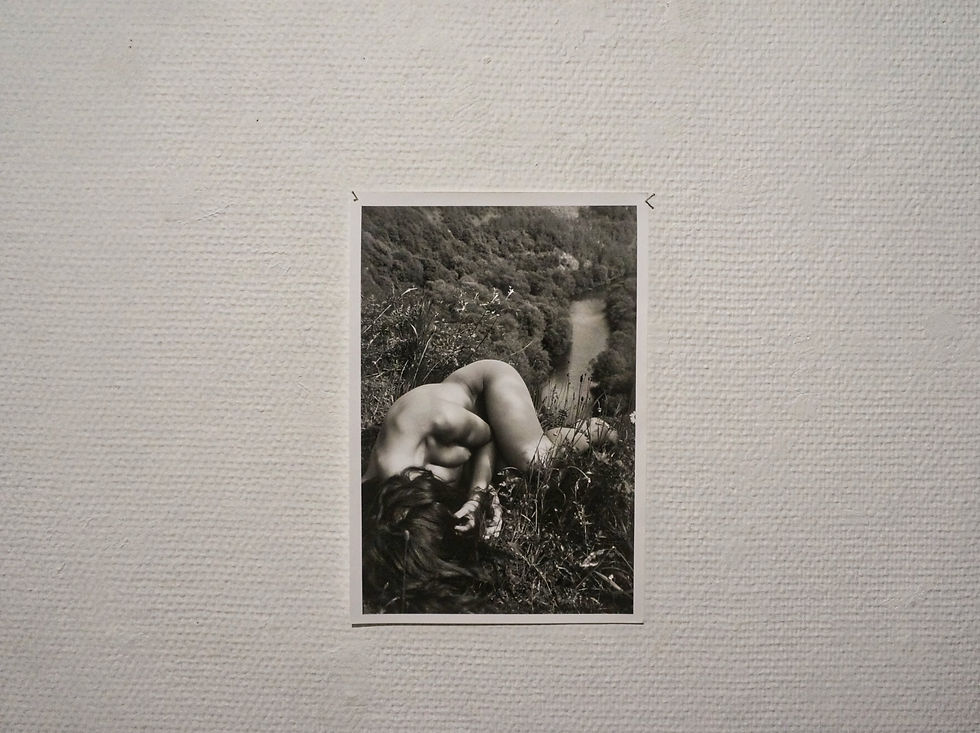

For Jean-Marie Boland, the female nude is not an object of contemplation, but an occurrence within the world itself. It does not confront the gaze, it settles into it, like light taking the time to find its place. Nature, here, is no setting; it is a continuation of movement, a living surface where skin and leaf share a single respiration. The image emerges from this delicate equilibrium between abandonment and resistance, the fleeting moment when flesh meets earth without vanishing into it. At first glance, one perceives death: these faceless bodies, lying amid the landscape, appear breathless, surrendered to the stillness of things. Limbs blend into soil, flesh dissolves into light, and all suggests an ultimate immobility. Yet around them, life persists, the air moves, leaves stir, matter pulses. The tension between bodily stillness and worldly vibration constitutes the true rhythm of these photographs. The face, that locus of individuality, is absent; the body, freed from identity, becomes pure form, nothing but light.

It is within this interval that kairos arises, the right moment, the one that never repeats. Not as a victory of the photographer over reality, but as a silent accord with it. In Jean-Marie Boland’s work, it marks the instant when light recognizes the body, when matter consents to become image. What photography captures is not a fragment of time, but the very encounter between time and radiance. The image preserves the trace of that collision: a spark, a flash, the pulse of a world revealing itself even as it withdraws.

In Boland’s work, the absence of clothing marks above all a departure from civilization. The naked body, stripped of the signs of social belonging, no longer belongs to the human world : it finds itself cast out of the polis, returned to the matter from which it came. Nudity here is not an ornament but a condition, the state of a being divested of all language, confronted with nature without mediation. Clothing, in covering, also protects, yet it inscribes humanity within the order of symbols: it declares function, role, gender, and place. Its absence suspends that belonging. The body photographed by Boland becomes anonymous, without status, without voice. This return to nakedness is a return to nature, a reintegration into the texture of the world. The body is no longer a civilized subject but a living form among others, skin exposed to light, to wind, to stone, to the bite of the earth.

Each image carries within it the tension of the human condition: a fragile flesh confronting nature, a spark resisting darkness. In Boland’s photography, vision is not a triumph over the world but the evidence that the visible still endures. His work bears witness to what persists on the edge of disappearance, to that relentless clarity which sustains the memory of the living.

For Michel Hanique, the intimate is not a subject to be explored but a space of expression. It is not a matter of composing a scene, but of allowing life to manifest itself as it is, in its rhythm, its light, and its gestures. This nudity follows no aesthetic of pose; it arises from a tacit accord between body and place, as if, in the absence of any social role, each person recovered the possibility of existing in the open. In this series, nudity also becomes a tool for radical equality. Whether anonymous figures or recognized personalities, all are brought back to the same measure, that of the body. The social garment, which hierarchizes and distinguishes, disappears here in favor of a shared truth. Skin reunites what function separates; it abolishes symbolic distances to recall the primary evidence of a shared condition.

This stripping away releases a form of individual poetry. The domestic space becomes an extension of the body, a territory where subjectivity circulates freely. Intimacy ceases to be a refuge; it opens, it is shared, it offers itself to sight without ever being fully given. It no longer resides in the flesh but in the place itself, in the way each person asserts their presence, their disorder, their light. It is no longer the body that is revealed but the manner of inhabiting, of moving, of leaving a trace within familiar space. These photographs do not respond to the curiosity of the gaze; they displace it. Rather than satisfying a desire to see, they open a field of questions. The mystery is no longer that of being, of what one is through matter, but that of doing, of what one performs in the continuity of simple gestures. The body is no longer the object of revelation but the witness of an interrupted action, of a movement suspended by the photograph. A hand, a shoulder, a barely outlined step, each fragment carries the memory of a gesture that endures within the image without ever fully coming to completion.

The black-and-white compositions are answered by another series in color, where clothing reappears and alters the very nature of perception. The body is no longer offered entirely to the light but fragmented, partially concealed, slipping between skin and fabric. The garment, far from being a mere accessory, becomes a visual device that interrupts the immediate reading of the body, introducing resistance and opacity that restore depth to the image. Where nudity established a form of self-evidence, almost an equality of presence, the fragment reintroduces absence and distance. Through a tighter framing that blocks a complete view, Hanique draws the viewer into a different kind of experience, not that of contemplation but of imagination. Deprived of totality, the eye is compelled to invent, to extend what it cannot see, to think the body rather than to possess it through sight. Some photographs, traversed by blurs and barely restrained movements, seem to capture a moment already vanishing. They place photography within a double order of reference, that of the machine and that of memory. On one side, the camera imposes its frame, cutting and fixing; on the other, the image resists this immobilization and drifts toward recollection, toward that particular indeterminacy proper to reminiscence. This blur functions as a metaphor of passage, between presence and its fading, between photographic reality and the mental trace it evokes. Thus Hanique does not capture the instant, he recomposes it; his images oscillate between the precision of the apparatus and the fragility of memory, between the objective gaze of the machine and the inward vision of remembrance.

In Didier Gillis’s work, the photography of the nude unfolds in an almost baroque register where the body becomes a stage. Here, intimacy is no longer whispered but proclaimed, set before us in a light that is dense, carnal, and dramatic. The female body is not merely represented; it is performed, it acts within the image, asserting itself as a figure that is at once delicate and sovereign. Everything in these photographs contributes to a dramaturgy of vision. The heightened contrasts, the deep shadows, and the monumental framing confer upon the flesh an almost sculptural power. The models appear as shifting invocation, poised between myth and reality, between body and symbol. In this staging of the body, clothing returns not as a modest veil but as a partner in play. Sheets, fabrics, and even tattoos become extensions of gesture, surfaces on which light captures the tension between surrender and control. Nudity here is never absolute; it is deliberate, measured, and fragmentary. It negotiates itself through material, inventing itself in the interstices. It is a chosen nudity, one that does not expose itself as revelation but composes itself as form.

The monumentality of Gillis’s work fully participates in this grammar of presence. The imposing formats, the density of the blacks, and the proximity of the bodies create a tangible encounter with the image; one does not merely contemplate these images, one enters them. The body becomes almost an architecture, a façade of stone and light. Each curve, each fold, each shadow takes on the weight of relief. This scale grants nudity a singular authority. It is no longer an object of observation but a space of affirmation. The nude does not present itself in the discretion of detail; it asserts itself through verticality, through frontality, through the claim of its own materiality. This monumentality diverts the gaze from any immediate eroticism and situates it before a symbolic power, that of the body as totem, as sign, as witness to the struggle between being and its image. The woman, often standing and hieratic, takes the place of the monument, not frozen, but composed.

Everything seems to move toward a reversal of the relationship between the image and the one who looks at it. The image does not seek to be contemplated; it seeks to impose its presence. This silent domination stems as much from the monumentality of the body as from the absence of gaze. Most of the models avert their eyes or conceal them, depriving the viewer of any direct exchange. This refusal of eye contact overturns the usual hierarchy of vision; it is no longer the spectator who observes, but the image itself that asserts its authority, inviolable and closed upon its own being. Within this staging of the visible, one senses a Hegelian tension between photographer and model. Each depends on the other to exist within the image, yet it is the work that ultimately prevails over both and over the viewer. It becomes an autonomous consciousness, a gaze without a face, a power without origin, the victorious form of the visible over the one who believes he possesses it.

Things to think about :

To extend the visit and deepen the reflection, here are a few questions that invite contemplation on the tensions running through this exhibition: those between the body and its image, between the visible and what eludes it, between the gaze and what it transforms. These questions are not meant to be resolved but to accompany the viewer during their journey :

What happens when a body becomes image: does it free itself or surrender ?

If clothing civilizes, what does nudity do ?

Does the image prolong life, or merely orchestrate the survival of the visible ?